- トップページ

- Fantastic Voyagers

- Strange but true: Jumping eggs

Investigating how things you thought were familiar really work can be a way of turning a new page in science.

Two scientists started paying attention to spinning boiled eggs and made some astonishing discoveries.

Hardboiled eggs have a more stable center of gravity than raw eggs, and as everybody who has tried it knows, if you spin them on a tabletop, they keep on turning. But what would you say if somebody told you that “if you spin them fast enough, they briefly float up in the air.” You may be thinking that I’m pulling your leg, but it is actually a scientifically proven fact.

When boiled eggs spin at high speed, their center of gravity rises so that they naturally “stand up.” But why does this happen? In order to solve that riddle, Professor Yutaka Shimomura of Keio University started collaborating with Professor H.K. Moffatt of Cambridge University. Not only were they able to explain the mechanism of how spinning eggs stand up, they also predicted that if a boiled egg spins at more than 30 rpm, it will even levitate for an instant.

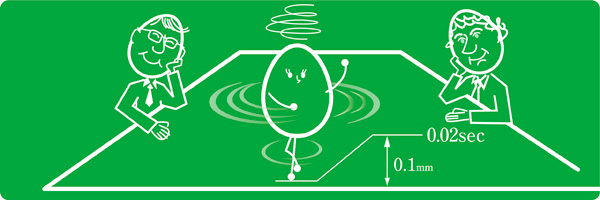

However, the height the egg will jump is at most around 0.1 mm and the time is shorter than 0.02 seconds, so we’re really talking about an extremely brief moment here.

When they presented their research in the science magazine Nature, it became big news. However, this was still only a story of “what theoretically should happen.” Someone had to try to make the experiment for real, and that someone was Professor Toshihisa Nishioka and his group at the Structural Strength Simulation Engineering Laboratory of the faculty of Maritime Sciences at Kobe University. Not coincidentally, their research was called “Project Eggs.”

Professor Nishioka’s group used computer simulations to study a numerical model of boiled eggs, This enabled them to analyze the egg’s behavior down to each millionth of a second.

Their results proved that the prediction of Professors Shimomura and Moffatt had been correct, and they were additionally able to show that a pear-shaped object would also float up in the air in the same way. Note that spinning an egg as fast as 30 rpm by hand is not possible, so they used a special device.

Furthermore, with the aid of an “argon pulse laser-synchronized ultrahigh-speed video camera system” they were finally able to capture photographic evidence of a levitating egg. (And it really does float in the air!) The airborne time was indeed 0.02 seconds, just as Shimomura and Moffatt had predicted.

Now, some of you may wonder what the practical use of this research might be. It is not as if it will lead to the development of an anti-gravity device of the kind that pops up in science fiction stories any time soon. However, taking a fresh look at familiar objects and asking “Why? How?” and then investigating and analyzing the mechanisms, that’s what the true pleasure of science is all about. Just like in the anecdote about Newton’s apple, this is how science has progressed up to where we are now.