- トップページ

- SUPER SENSORIUM

- A Visit to the Biodiversity Center of Japan – Something important that should be better known –

A Visit to the Biodiversity Center of Japan

Something important that should be better known

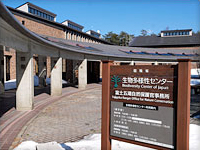

A few minutes along the road from Lake Kawaguchiko to the Fifth Station of Mt. Fuji, in the forest at the foot of the mountain, lies the Ministry of the Environment’s “Biodiversity Center of Japan.” When we visited in early March, the treetops of the surrounding red pine forest were still covered with snow. We immediately felt that this was a very different natural environment from the big city.

“People tend to think that biodiversity is something that only the Ministry of the Environment deals with, but in fact each ministry and agency is currently promoting their own measures. There are about 660 of these measures, so we are literally mobilizing the whole country,” says Naoko Nakajima of the Nature Conservation Bureau, Ministry of the Environment. “Obviously, it’s not just a problem for the government. We need to get local authorities and the private sector involved as well, since the necessary measures varies in each region.”

Certainly Japan has a wide variety of ecosystems, from Hokkaido in the north to Okinawa in the south, and it would be impossible to resolve all the issues facing each region in a top-down fashion. First we need to become aware of the problems in the nature closest to us, and then apply suitable measures for that particular area.

One thing Ms. Nakajima mentioned that has stuck in the mind was how biodiversity affects culture. “The countless local specialties from all around the country also depend on a diversity in biota.” Many of the local products we used to stuff our bellies with as kids have now become luxury items. If for example the rice plant were to become extinct, Japan’s sake culture would likely vanish along with it.

The Biodiversity Center of Japan is surrounded by virgin forest at the foot of Mt. Fuji.

Naoko Nakajima of the Nature Conservation Bureau, Ministry of the Environment

Meanwhile, “biodiversity” is still not exactly a household word. This is also a problem. “Maybe it’s because it’s such an abstract word. It’s hard for ordinary people to grasp the sense of danger. It’s not like pollution, for instance, which directly affects our daily lives.” Consequently, one of the goals is to raise the awareness of biodiversity to at least 50%. “First we need to make it a widely-discussed topic. People need to talk more between themselves about biodiversity. Critical opinions are also welcome, of course.”

Regarding the issue of global warming, it took about 10 years for the awareness of the need for CO2 reductions and recycling to penetrate the general public after the 1997 COP3 climate conference, which was held in Kyoto. The COP10 conference on biodiversity was held in Nagoya in 2010, and the commitment to biodiversity is also gaining momentum.

Many people are interested in helping out, and in the past the Biodiversity Center has conducted several surveys of “living things close to home.” These were public participation programs that were part of the National Survey on the Natural Environment (Green Census). With the help of nature lovers all over the country, the distribution and ecology of familiar plants and animals known as “environmental indicator species” were investigated – swallows, burs, cicada husks, and so forth. For example, over 25,000 people participated in a survey back in 2000 – 2001 on the theme of “nearby forests.”

Another project that examined the effects of global warming was called “Ikimonomikke” and ran from 2008 to 2013.. The research themes and methods varied with the seasons, and anyone could join in just for fun. The participants observed living things and natural phenomena, and then simply sent in their results via their mobile phones, mail, or the project’s web site. The collected information was then published on the web site. All the small signals sent out by the various creatures noticed in this project will hopefully provide an opportunity to take a new look at their unique modes of life.

In the library’s reading room, you can view extensive materials and samples related to the conservation of the natural environment and its flora and fauna.

In the permanent exhibition room, you can learn the basics of biodiversity from the many objects on display.