From symbols to characters

Among the most important elements in order to form a culture, tools and language are the first that come to mind. Maybe we should add fire to that short list as well. Tools have been made and used in the Japanese isles for a very long time, and Jomon pottery is one of the oldest forms of earthenware in the world. Without a doubt, the people of the Jomon period (from approximately 15,000 years ago to 2300 years ago) used language too. However, until Chinese characters were imported from the continent in the 5th century AD, Japan had no real writing system of its own.

Already in the world’s oldest known cave paintings in the Chauvet Cave in France (from approximately 32,000 years ago) there are what appears to be signs or symbols. Similarly, there are also symbol-like marks engraved in Jomon earthenware and in the bell-shaped bronze vessels of the subsequent Yayoi period. There is even a theory that some of the patterns on Jomon pots tell some sort of story. However, even if they might be a kind of prototypical “characters,” they are still not proper characters with a regular correspondence to (spoken) words.

Patterns on a Jomon pot. Jomon earthenware were the first vessels (utsuwa) on the Japanese isles.

There are various indigenous Japanese writing systems that are sometimes claimed to be from ancient times: Katakamuna characters, Tsukushi characters, Ahiru characters, cursive Ahiru characters, Izumo characters, etc. Collectively, these are known as Jindai moji or Kamiyo moji – “characters from the Age of the Gods.” However, most scholars agree that these writing systems were created – or fabricated – after the introduction of Chinese characters, or even in more recent centuries.

The introduction of written characters from China must have been a considerable shock for the preliterate people of the Japanese islands. As the research of Professor Shizuka Shirakawa has shown, the Chinese characters themselves were full of spells and sorcery. They were above all magical, mysterious tools.

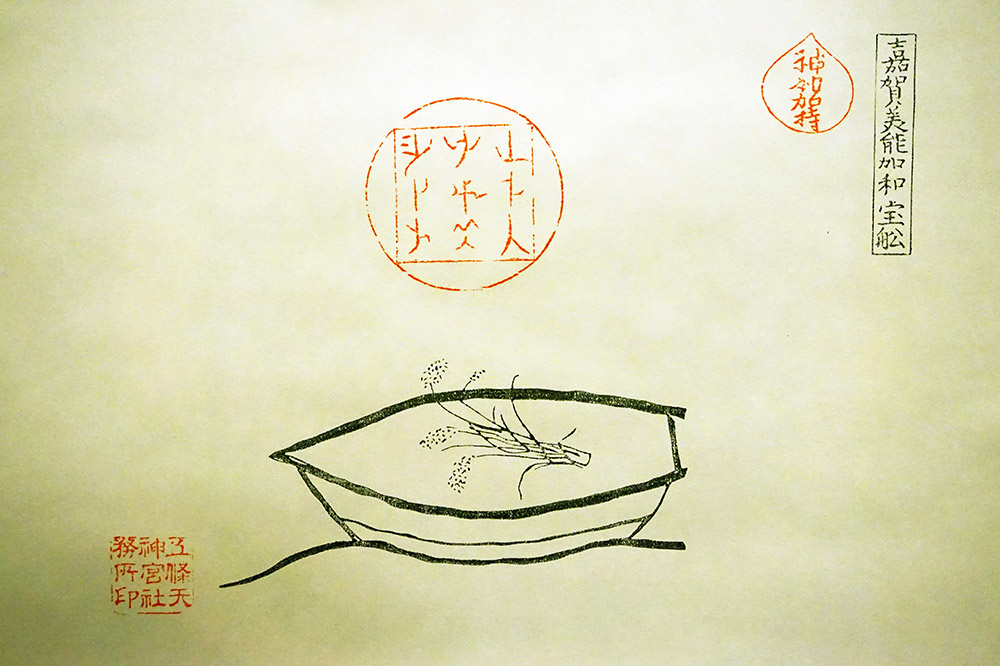

Ancient image of a treasure ship from the Gojoten Shrine in Kyoto. The characters inside the round, red seal are Jindai-moji.

A country without writing but with kotodama

During the 7th – 8th century Manyo Period, it was frequently emphasized that Japan was a country “where the soul of words bring happiness to the land.” There was an ancient belief that words carried spiritual powers (kotodama), and when confronted with the magic spells of the Chinese characters, the Japanese seem to have been made strongly aware of the spiritual force of their own spoken language. The power of sacred sounds versus the magic of writing, as it were.

Words are ways of cutting up the world. For example, by naming them, we separate the sky from the earth, and clouds, stars and the sun from the sky. Continuous time and space is divided by the voice. That is to say, words were also the first analytical tools. Logograms such as Chinese characters are also a way of visually dividing, articulating and analyzing the world.

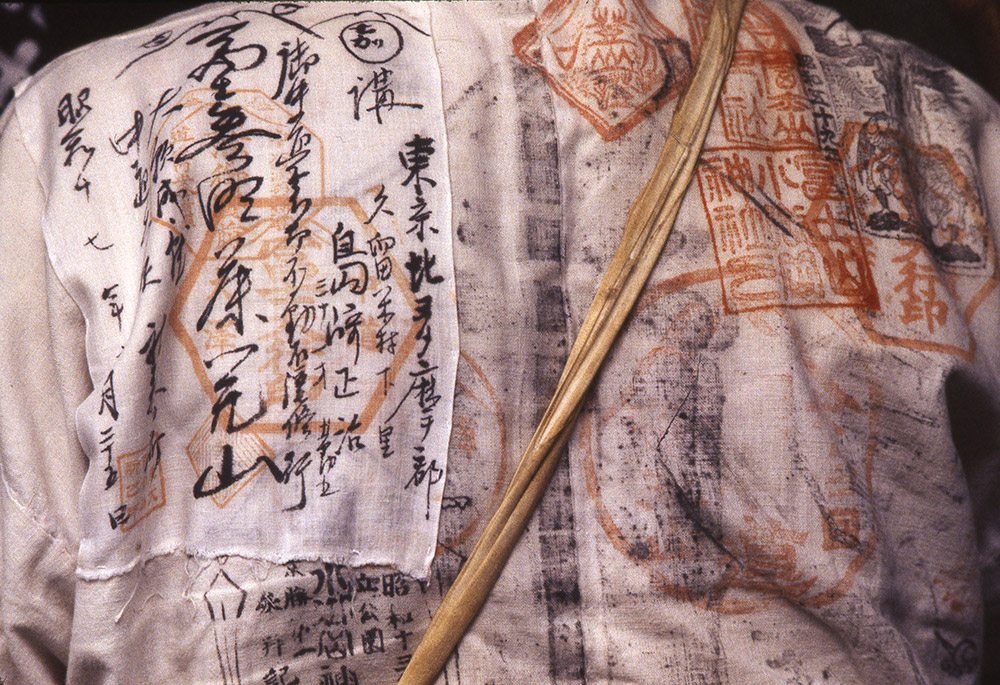

White garment worn by participants at the opening of the climbing season at Mt. Fuji. It is covered with seals and characters that purify and protect the wearer’s body with their magic power.

The complicated Manyogana system

The 8th century Manyoshu (an anthology of poetry) and Kojiki (“Records of Ancient Matters”) are two of Japan’s oldest books. They became venues to explore these “analytical results.” The writing system known as Manyogana was a grand attempt to replace the spiritual power of spoken Japanese words with the magic of Chinese characters. Strangely enough, the Japanese at the time seem to have mixed two contrasting methods from the very start. On the one hand, Japanese sounds were matched with Chinese characters (kanji) with the same sound. But at the same time, kanji were also matched with Japanese words according to their meaning. These dual methods eventually lead to what is now called the on-yomi (“Chinese reading”) and kun-yomi (“Japanese reading”) of kanji. The notion that each character can correspond to several different sounds is one of the unique features of the Japanese language.

As if that was not enough, the Chinese pronunciation of characters changed over time and with geographical region, and since Japan imported a mixture from the Wu, Han and Tang periods among others, the on-yomi were far from consistent. And not only did the words expressed with the kanji have many homophones, each syllable in the traditional spoken “Yamato Japanese” was also often associated with several different meanings. For some reason, the Japanese chose to introduce this extraordinarily complicated system from the very moment they started to use writing. Written Japanese has great latitude in both sound and meaning, and the correct meaning and pronunciation needs to be determined on the spot from the context. It is a bit like watching the world through a microscope where you constantly have to adjust both the eyepiece and the objective lens to keep the subject in focus. This latitude and context-dependency has had a tremendous influence on Japanese sensations and logic ever since.

In cultures with alphabet-style writing systems, on the other hand, the basic principle is that each letter or sequence corresponds to a specific sound. In practice, it is not quite that easy, of course. There are letters that are not pronounced, and languages like English where the one-to-one correspondence between sounds and letters it not very closely observed, but the latitude is still far smaller than in Japanese. It is more like looking at the world through a standard pair of glasses, as it were.

Koto, mono and uta

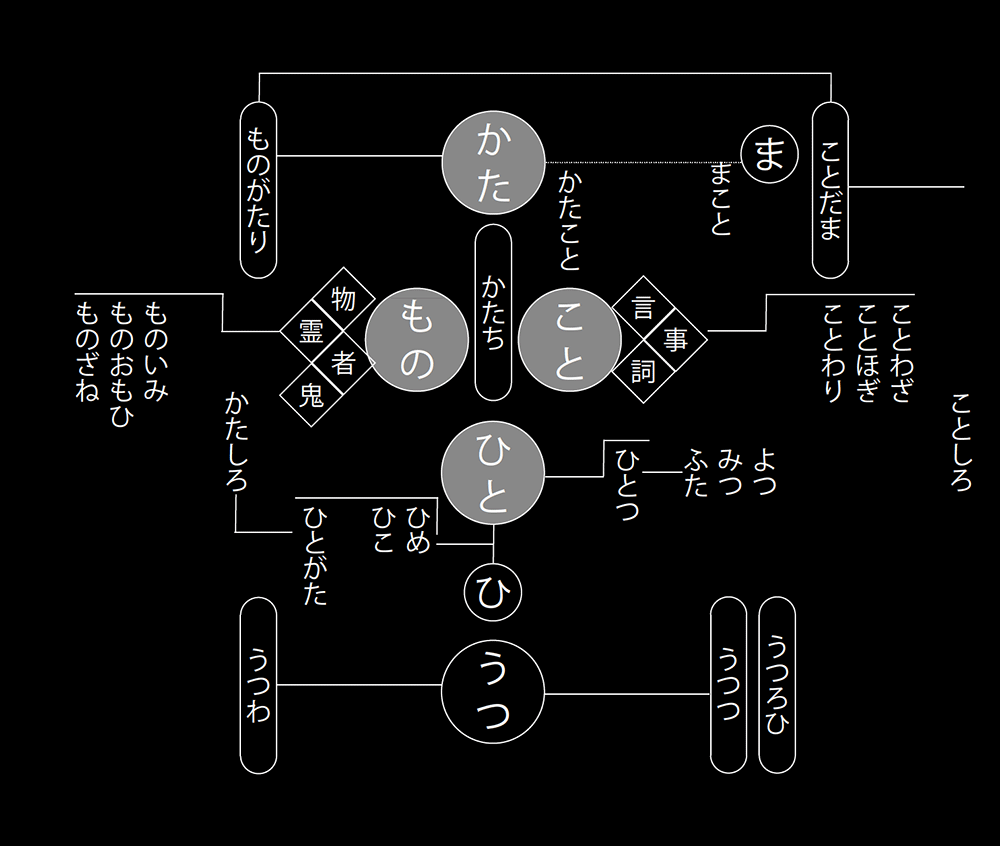

In the old Yamato Japanese, koto and mono are two central concepts. Koto refers to matters and affairs, while mono refers to objects and people, and sometimes to spirits and demons as well. Just as koto is not simply “facts,” mono does not necessarily mean physical objects.

The “demonic” meaning of mono lives on in its contemporary use as an intensifier in words like monosugoi (“tremendous”). The word monogatari, which now simply means “story,” used to mean a tale about the origin of ghosts and spirits. The many stories of mononoke (vengeful spirits or monsters) that flourished in the Middle Ages were about mono that had become physical objects but then regained their souls.

Edo painting of a “vessel goblin.” Spirits were believed to dwell in tools that were over a hundred years old.

The saying that “the soul of words bring happiness to the land” also meant that “spirits (mono) and words (koto) bring happiness to the land.” Unique linguistic techniques and a peculiar know-how evolved as well. Koto-age (something that is explicitly mentioned), koto-wake (an explanation that stresses the original function of a word), and koto-yose (where a word functions as a hub in a network) are some examples, but it was above all in songs and poetry that all these linguistic techniques were condensed. Utamakura (“song pillows”) were a kind of poetic words, often place names, that alluded to famous scenes and figures, makurakotoba (“pillow words”) were stock epithets that magically connected words, while kakekotoba (“pivot words”) played on the different meanings of characters with the same pronunciation.

Diagram of words and concepts related to mono and koto in Yamato Japanese.

The birth of Japan’s own characters

The people of the land of kotodama did their best to match their words with kanji, but the Chinese characters themselves were both magical and rational at the same time, and there were peculiar nuances of Japanese that were hard to control. There were feelings and sentiments that just couldn’t be captured with the kanji, and on the opposite side of the coin, some characters were too potent and meant too much. This conflict led to the creation of syllabic kana characters in the early Heian period. Hiragana in particular was a major step that might be called the invention of Japanese as a written language. On the Chinese mainland, the history of characters had its roots in marks carved in bone and stone. In Japan, however, characters were written with brush on paper from the very beginning. Chinese characters were firm and supposedly universal, while the Japanese ones were always pliant and flexible. The birth of soft hiragana was perhaps inevitable.

One of the major features of the Japanese language is that it is written with a combination of three character sets at once: hiragana, katakana and kanji. This system gradually became general. In modern times, Arabic numerals and Roman letters have been added to the blend. The mixture of on-yomi and kun-yomi readings, and multifarious characters of different origins gives both written and spoken Japanese a logicality (or illogicality) that is not readily grasped by Western logic. Japanese is sometimes accused of being vague and ambiguous, but that aspect is rather a proof of the language’s multilayeredness, its integration of multiple senses and logics of different origins.

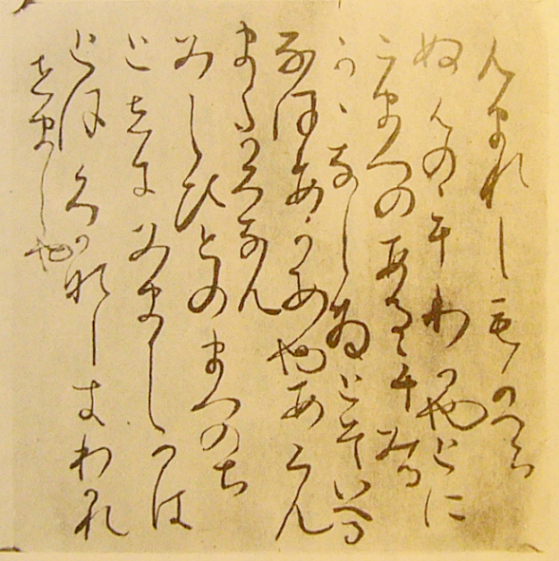

Tosa Diary in kana characters. Faithful copy by Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241) of Ki no Tsurayuki’s original handwritten 10th century manuscript.

The empty world

Along with the advent of the fluid hiragana style of writing, the notion of utsuroi (transitoriness) entrenched itself in Japanese aesthetics. Maybe ancient feelings that had long been confined by the strict and square kanji were revived by the new kana characters.

Utsu was an old word that referred to caves and hollows. It meant emptiness, the sky, and also depression. Earthenware, bronze bells and other tools that were empty inside were utsu or utsuro, which eventually became utsuwa (“vessel”). Since they were empty, you could put something in them, or something could enter. The sound of the wind blowing into an empty vessel was called otozure, which means “visit.”

It was also a way to invite gods and spirits. It is no coincidence that the sacred object of worship at Shinto shrines is often an empty box or container, or that the structure of a shrine itself is basically empty. It was precisely because it was empty that the gods could dwell inside and demonstrate their mysterious powers, or so it was believed.

A temporary space to greet the gods, other than at a regular shrine or household shrine. The area inside the ropes is kept clean and empty.

From utsuroi to wabi-sabi

The gods and spirits who visited the empty space or vessel (utsu) eventually departed again. They were transitory (utsuroi), and transitory things were considered beautiful (utsukushii). The birth of hiragana and the entrenchment of the Buddhist idea of the “evanescence of all things” in the Heian period increasingly fueled the sensation and aesthetics of transitoriness. The catchphrase “Flowers, Birds, the Wind, and the Moon” was invented as a symbol of the Japanese view of nature and sense of beauty. Flowers are scattered, birds fly away, the wind blows away, and the moon wanes. All of them are transitory.

In the middle ages, aristocratic culture fell into decline. Many of the buildings and craftworks created by the aristocrats lost their patrons in the repeated wars, and crumbled into dust. As the vanity of life seemed ever clearer, people came to find an inverted sense of beauty in ruined things, rusting, withering things. This was the aesthetics of wabi, sabi and yugen, the beauty of transitoriness taken to its extreme.

Beyond segmentation and analysis

The technique of printing with moveable type was imported from China toward the end of the Warring States period (15th-16th century). Tokugawa Ieyasu experimented with publishing books printed with wooden type, but that remained an exception. Throughout the Edo period, moveable type played no role in the mainstream of Japanese publishing. While guns from the West quickly caught on, the lack of interest in moveable type was probably because the idea of individual units of type didn’t fit the uninterrupted Japanese writing style with its mix of kanji and kana characters, not to speak of its sense of utsuroi. Although the Japanese were using kanji, they had already developed a written culture of their own, and moveable type was not so easy to adopt as the characters themselves had been a thousand years earlier. Full-scale use of printing type had to wait until after the Meiji Restoration and the active reception of Western culture.

Words and letters arise from a need to divide the world. However, Japan’s character culture, as symbolized by hiragana and the sensation of utsuroi, almost seems to have harbored a desire to return to the flowing, transient world.

There is no doubt that segmentation and analysis are indispensable tools for grasping the world. But the moment you divide the world, there are always things that fall through the cracks. Or perhaps the result of the segmentation is a world that is hard to grasp with a logic that can be spelt out in words. The Japanese sense of language – or sensory logic – is complicated and may sometimes seem incomprehensible, but it might also hide the key to a world we have lost sight of, or approaches to new worlds we have yet set eyes upon.

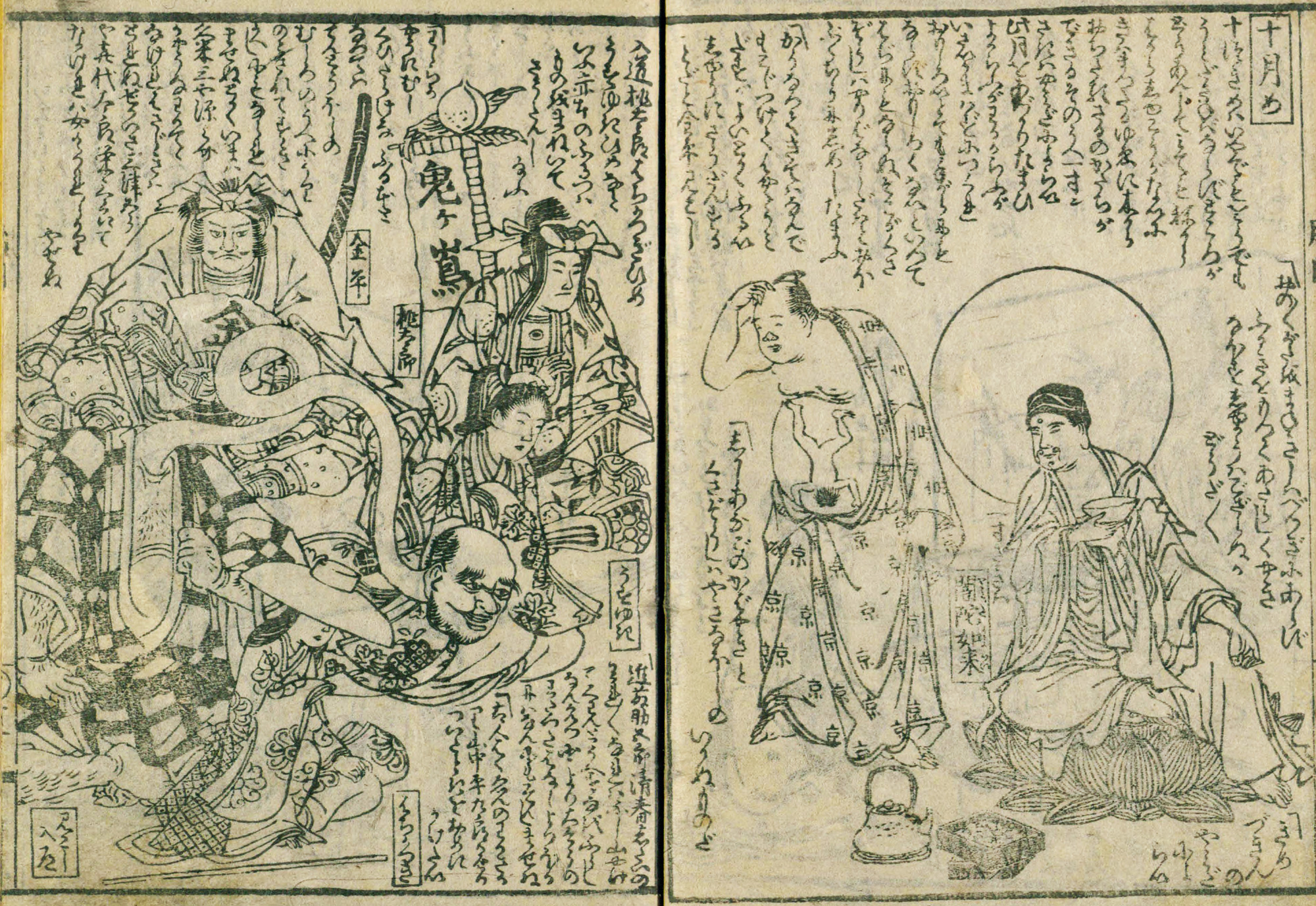

Edo period publications did not use movable type. From Sakusha tainai totsuki no zu (1804), a novel about the life of a novelist by Santo Kyoden (1761-1816).